Baroque String Playing / Giga from J S Bach's Partita no. 2 in D minor for solo violin, BWV 1004 /

Phrasing and Articulation

Metre

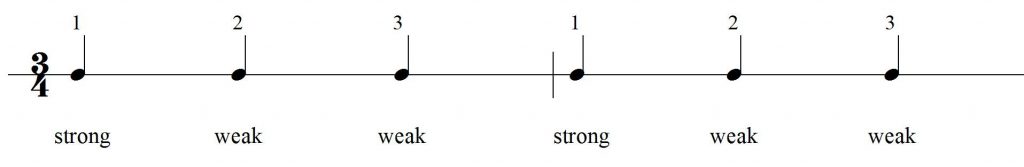

When thinking about how to articulate a piece of baroque music, it is helpful to consider its metre (i.e. the number of beats in each bar, and the varied emphasis given to each beat). As you might expect, not every beat of the bar carries equal weight. A duple time signature would usually imply a pattern where the first beat of each bar is considerably stronger than the second. A quadruple time signature (such as in this Giga) often requires a strong first beat, a weaker second beat, a strong third beat and a weak fourth beat.

The composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier, writing in 1692, explains this quite succinctly:

"Note that there are strong and weak beats in music. In a measure with four beats, the first and third beats are strong, the second and fourth are weak. In a measure with two beats, the first is strong and the second is weak. In a measure with three beats, all the beats are equal; if desired, the second and third can be weak, but the first is always long."

This information gives us a good principle to build upon when shaping a piece of baroque music. It is not, however, the full story. Playing a piece in which every bar follows exactly the same pattern of strong and weak beats wouldn't be particularly interesting. We need some other pointers to help us phrase the music.

Dance steps

In musical styles that originated as accompaniment for dancing (such as the movements from Bach's suites and partitas), the steps of the dance influenced the metre and the implied hierarchy of beats in each bar or metrical sequence. For example, a characteristic feature of many sarabandes (usually in triple time) is an emphasis on the second beat of some (but not all) bars of the piece. (Nick looks at Sarabandes and their metre here ) A minuet often (but not always) has a metrical structure which works over two bars: strong - weak - strong - strong - strong- weak. This mirrors the pattern of the dance, where the performers take steps on the first, third, fourth and fifth beats of the two bar pattern, making little bends on the second and sixth.

Harmonic rhythm

Composers often mark the beat hierarchy through the music's harmonic rhythm (the harmony often changes on the strong beats of the bar). If the harmony changes significantly on what is normally a weaker beat, particularly if it introduces a dissonance, this may be a case for deviating from the general rule and giving the beat more emphasis, either with a louder dynamic, or by 'placing' the note (making a tiny break before playing it).

Thinking about the music's harmonic rhythm can help you determine the pattern of strong and weak beats, even if you do not know anything about the steps of a baroque dance. It also helps you identify features such as a hemiola, often occurring at cadences in baroque music, where two bars in triple time are articulated as if they were one bar at half the tempo. Performers play the first long beat of a hemiola strongly, giving less weight to following two long beats (which effectively means playing any notes that fall on the first beat of the second bar of the hemiola lightly).

becomes

Video Resources

In this clip, Helen looks at the harmonic rhythm at the beginning of the Giga's second section, in order to help determine which notes to play strongly.

Ruth explores harmonic rhythm in some detail in her discussion of movements from Bach's G-major Cello Suite. Click here to learn more.

Tessitura

When we raise the volume of our spoken voice, we tend also to raise the pitch. Playing louder as a phrase gets higher is one method that eighteenth-century string players recommended in order to imitate speech in their music. This is particularly relevant when playing a sequential passage that gets higher by degrees; we can play each repetition of the figure louder as the pitch increases.

Video Resources

Making space and punctuation

Many baroque composers and theorists talk about music in terms of words and sentences, where a complete musical 'sentence' (concluded by a cadence) may be seen as made up of smaller phrases (sub clauses or even individual words). Just as a speaker would breathe at commas and full stops, so a piece of music needs its own punctuation. Where composers from later periods often indicate breathing space with a rest or a comma, baroque composers tended to leave it to the intuition of the performer. The fact that there are no rests in a piece doesn't mean we don't make any breaks!

Our music makes more sense if we include punctuation points, but, we don't want to interrupt the flow by introducing a lot of 'stopping and starting'. In order to introduce some punctuation into your performance, you may find it better not to play every note to its full length. For example, it may be advisable slightly to shorten a long note at the end of a phrase in order to make some space before beginning the new phrase; thus allowing the music to breathe without interrupting the underlying pulse. This, of course, is what a singer or wind instrumentalist has to do in order to keep going!

Video Resources

Another way to add space to the music is by playing ends of phrases softly, then increasing the intensity at the beginning of the following phrase, as Helen does in this example.

Video Resources

In this clip, viola player Nick Logie demonstrates the importance of allowing the music to breathe.

1 - Bowing

2 - Slurs

3 - Phrasing and Articulation

LEARNING RESOURCES

1.

What is historically informed performance practice?

An introduction to historically informed performance practice of baroque music, and a look at period instruments and bows.

2.

Allemande from JS Bach's Suite no. 1 in G for unaccompanied cello, BWV 1007

Ruth Alford explores this movement in the light of other baroque music for 'cello.

3.

Giga from J S Bach's Partita no. 2 in D minor for solo violin, BWV 1004

Helen Kruger looks at what what baroque theorists had to say about bowing, phrasing and articulation and applies it to this movement.

4.

Largo and Allegro from G P Telemann's Viola Concerto in G, TWV51:G9

Nicholas Logie discusses phrasing, ornamentation and vibrato.

5.

Further Reading