OUR STORY

The Creation of the National Centre for Early Music 1997-2000

Chance and opportunism play a good part in most human enterprises – and never more so than in the creation in York of the National Centre for Early Music in St Margaret’s Church, under the auspices of the York Early Music Foundation.

The opportunities arose, however, because a programme of quality already existed, capable of further substantial development; because a number of institutions and individuals in York and elsewhere were willing to back the idea; and because we had Delma Tomlin, a director of exceptional talent and a group of working Trustees with relevant skills and experience – to a high degree – in the legal, financial and management aspects of major capital projects Dick Stanley, Mike Taylor and Roger McMeeking. Then the National Lottery, with other backers, made it possible.

Even so, we nearly failed. This account attempts to explain what went right, what was difficult, and how we got there in the end. It is written from the point of view of the Trustees, but I hope it reflects also the contributions of the other parties to the project, and the problems they faced in their turn.

We would be glad to respond to requests for more information from any source.

Robin Guthrie

Chairman of York Early Music Foundation, 1994–2001

OBJECTIVE

This paper is intended as a post-project evaluation of the National Centre for Early Music (NCEM) project, following its formal opening in April 2000. The objective is to learn from experience of the project and to improve the quality of future projects for all the participants. Technical evaluations and user-satisfaction evaluations will contribute to the assessment in the future, while feedback will contribute to future design briefs and to the methodology of procurement.

INTENDED AUDIENCE

The evaluation is intended to be of interest and relevance to:

- construction clients and potential clients;

- construction professionals;

- funders and sponsors of capital projects in the arts;

- all involved in the improvement of quality and value for money in relevant capital projects.

As long ago as 1975, the York Civic Trust had taken over five redundant churches from the Diocesan Board of Finance, with a view to putting them to appropriate uses. They were let on 99-year leases, with an option for extension, at a peppercorn rent and with minimal repairing obligations. One church became an archaeological resource centre, and another a meeting place and activity centre for older citizens, and so on. St Margaret’s, Walmgate, however, was no more than a props store for York Theatre Royal. The Civic Trust accordingly invited the York Early Music Foundation Trustees in 1995 to consider the church as a possible site for the development of their activities. The Trustees had not been looking for premises, and in that sense the solution preceded the problem; on the other hand the Civic Trust’s offer opened up new possibilities for the Foundation to enhance its embryonic programme in ways that had not previously been envisaged.

METHODOLOGY

The project is assessed in the context of a conventional three-stage process:

- pre-project – statement of need, funding and Business Plan; organisation and project development; Strategic Brief; design team selection;

- project – validation and project brief; detailed briefs, Stage C and Stage D; Business

- Plan development and funding processes; construction;

- post-project – occupancy; commissioning and review; restatement of need;

- evaluation of process, product and performance;

followed by:

- conclusions and lessons for the future.

PRE-PROJECT STAGE

Statement of need and funding

York Early Music Festival was established in 1977 and rapidly achieved a national and international status. In 1994 York Early Music Foundation (YEMF) was formed, to provide support for the Festival. The intention was – and remains – to provide continuity between the annual Festivals by promoting additional events and developing a strong educational programme, together with greater financial certainty.

As long ago as 1975, the York Civic Trust had taken over five redundant churches from the Diocesan Board of Finance, with a view to putting them to appropriate uses. They were let on 99-year leases, with an option for extension, at a peppercorn rent and with minimal repairing obligations. One church became an archaeological resource centre, and another a meeting place and activity centre for older citizens, and so on. St Margaret’s, Walmgate, however, was no more than a props store for York Theatre Royal. The Civic Trust accordingly invited the York Early Music Foundation Trustees in 1995 to consider the church as a possible site for the development of their activities. The Trustees had not been looking for premises, and in that sense the solution preceded the problem; on the other hand the Civic Trust’s offer opened up new possibilities for the Foundation to enhance its embryonic programme in ways that had not previously been envisaged.

An initial Structural Survey of the church by a local architect was made available to the Foundation and a sketch layout was prepared by the same architect, showing how the church could be used as performance space. The Foundation Trustees, with the active encouragement of the Festival’s Administrative Director, Delma Tomlin, took the decision that the concept was worth exploring, if funding from the National Lottery could be obtained. A bid was prepared by the Foundation Trustees themselves (September 1995).

The bid included early drafts of a schedule of accommodation and of a Business Plan, with references to space for offices, rehearsals, recordings and conferences, as well as to performance and study:

Creating the National Centre for Early Music. A preliminary sketch drawing for feasibility purposes was also included, together with approximate costings:

Restoration (including professional fees)

£332,000

Alterations (including professional fees)

£595,000

Equipment

£229,000

Commissions

£95,000

Administration

£120,000

Inflation

£69,000

Total

£1,440,000

A National Lottery Arts Council Grant of £1,080,000 was sought, with matching funding of £360,000, from charitable and public sources.

There then occurred the most significant single event in the early development of the project. The Arts Council of England (ACE) commissioned Jane Priestman OBE to prepare an assessment of the project in July 1996. She had the vision to recommend an award greater than that applied for, specifically because:

‘A straightforward church refurbishment will not offer the Foundation that special magic it will require to match its own aspirations and its international position. For this reason the award should be raised to allow additional professional advice in areas of acoustics, interior architecture, urban and precinct design and landscaping.’

This highly perceptive recognition of the potential of the scheme (at a time when the church interior remained invisible because of the storage of stage props there) set the tone for the entire project from that point on.

There followed the working up of more detailed evidence of the programme of work to be undertaken and of the likely matching funding. The ACE Lottery Grant offered in March 1997 (and enthusiastically accepted) was £1,518,750, requiring £506,250 in matching funding, and a new all-inclusive project value of £2,025,000. That total remained unchanged until project completion.

The Grant was subject to 16 standard conditions and 10 special conditions, of which the most significant was that not more than £150,000 would be released until ACE was satisfied with the RIBA Stage D costings. The Foundation would be closely monitored.

The fund-raising was undertaken entirely by Delma Tomlin, as an essential pre-condition for the project to become reality. In the event, the required resources were raised from local and national sources, including £171,000 from English Heritage, £52,500 from the Foundation for Sport and the Arts, and £50,000 from the Garfield Weston Trust.

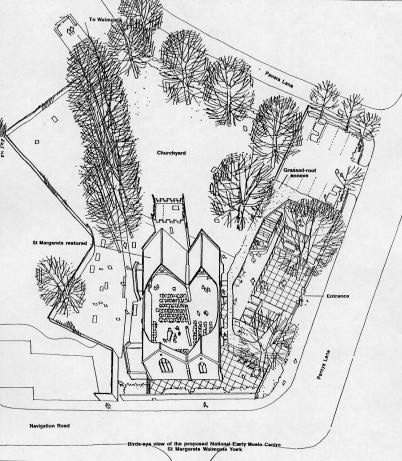

There then occurred a second defining event. The application for change of use caused some concern to the City Council as Planning Authority, because of the likely increase in traffic and the inadequacy of on-site parking. It therefore offered to the Foundation adjacent land in Council ownership, which squared off the churchyard, so that parking could be provided. At the same time, an arrangement was made with a neighbouring retailer for the evening use of its customer car park.

ORGANISATION AND PROJECT DEVELOPMENT

Once the Grant had been accepted, the Board of Trustees was augmented, and a start was made on raising the balance of the matching funding. At this point a small group of two Trustees was established to steer the project from close quarters and to back up the Administrative Director (whose experience was primarily in arts administration) in her role as the Foundation’s sole representative in all external negotiations. This group of Trustees was soon expanded to three: the Trustees’ Implementation Group (TIG). They brought a rare combination of legal, financial and client management skills at a high level, along with a willingness to devote considerable time and energy to the project. The role of TIG was crucial.

An early step was to commission a full Condition Survey of the standing building, with the objective of ensuring that all fabric repairs for the foreseeable future were incorporated into the construction project. The saddling of the fledgling organisation with a rolling repair programme into the future was to be avoided at all costs. The project budget was refined as issues such as VAT were clarified, and as the extent and probable cost of repair became known. A further step was to test the realism of the organisation’s embryo Business Plan, and to undertake market research into the critical areas. The project was under way.

Strategic Brief and Professional Team

The appointment of the Professional Team was accomplished with some difficulty. The change of architect (recommended by ACE) was initiated through the appointment by the Foundation of an experienced Architectural Adviser. The Adviser’s search of available UK expertise included visits to practice offices and projects, leading to the drawing up of a long list and then a short list to participate in competitive interviews. Concurrently, the ACE Build Monitor – Bovis – joined the TIG meetings.

Bovis had been appointed in May 1997, after the Grant announcement, but detailed terms of reference for its appointment were not provided by ACE until that August. Because the authority of the Monitor was not at first made clear, difficulties over the Professional Team appointments then ensued, leading to the requirement for a further competition for the post of Project Manager. This was symptomatic of the change in the Foundation’s relationship with ACE. No doubt arising from sharp criticisms of mounting Lottery project costs elsewhere, by the National Audit Office and the Public Accounts Committee, new ACE procedures were being introduced in 1997/8, but they were confused with procedures under which the NCEM Grant was initially awarded. The adverse impact of this circumstance persisted throughout the project (see 2.4 below).

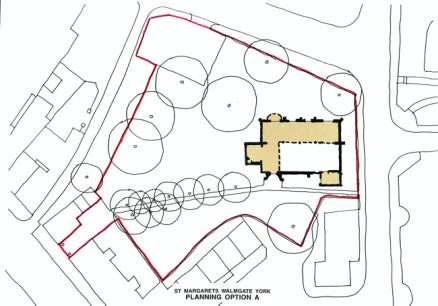

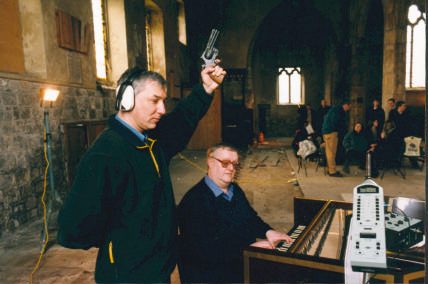

Acoustic tests in March 1998 confirmed that the best use of the excellent acoustics would be to keep the church as one performance space, as the plan below

During this difficult period for the project in the autumn of 1997, the Strategic Brief was drawn up, and approved by Trustees on 18 August 1997. It sought to develop the artistic ‘mission’ first articulated in the Lottery bid, and then to set the context for the practical activity to follow. It was designed to assist the Professional Team by establishing clear objectives for their work. It described sequentially the contexts of York, the Walmgate area, the Church, approaches and connections to it, and the architectural and landscape strategies that the Foundation wished to see adopted. It went on to express the Foundation’s cultural vision and the activities intended for the Centre, together with a design approach and a definitive statement of the inviolability of the budget. This exercise clarified the Trustees’ own thinking, and communicated precise requirements to the Professional Team – to serve as a measure for their future performance. There was to be no doubt as to the objectives to be achieved, and no opportunity for ‘hi-jack’.

The work of the Architectural Adviser led to competitive interviews, in September 1997. Design practices were provided with comprehensive written information, to supplement their verbal briefing, and invited to make presentations with members of the supporting disciplines to be included in their team. It was considered important that the composition and extent of each team should be specified in the first instance by the Lead Designer. This was because it was felt the project would stand or fall by the quality of its design and the extent to which the team members were integrated with each other. Tenderers were also asked to provide a lump-sum fee bid, both up to Stage D and for the project as a whole.

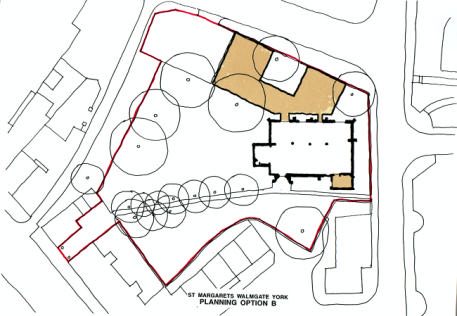

St Margarets Walmgate York Planning Option B.

A rather unusual circumstance then followed. After six interviews (including local and national practices), two proposals were considered to be of equal and outstanding quality, but one was at significantly lower cost. It was only after several weeks’ negotiation that it was established that the lower bid related to the pre-construction period only, and omitted the construction period completely. This discrepancy escaped the whole of the interview team, including the Monitor.

It would also have been helpful at this early stage if the Build Monitor at that time – one of four individuals appointed within the first 12 months – had attended the pre-interview review of tenders as requested, or indeed the interviews in full. Continuity, or better briefing of individual Monitors, would have reduced misunderstandings, and we learned early and painfully that Build Monitors were limited, by their role, to reporting to ACE, and passing on observations received from ACE.

It became apparent during these interviews that the majority of these architects felt that the best use of the site would be to keep the church itself as the performance space, and to site the reception area, offices, green room etc. in a newly built structure linked to the church – an interesting concept, but one that would have to be funded within the fixed budget.

By early December 1997, the brief and competitive fee bids for the role of Project Manager had been established, and Gardiner and Theobald (GTMS) were appointed. Its first task was to overcome the difficulties with the appointment of the Lead Designer, and by February 1998 van Heyningen and Haward and their team were in place. The cost of their services was higher than had been anticipated, but TIG was aware that the cost of the quality required might be high, and succeeded in persuading ACE to accept the redistribution of the budget that was required.

The team included full design services, Conservation Architect, access audit, structural and M&E engineering, acoustics and landscaping, and all expenses, at an all-inclusive fixed lump-sum fee representing 22.15% of the anticipated contract value. A separate and comparable cost to the completion of Stage D was also agreed. This approach was considered healthy in that it gave cost-certainty to all parties, allowing focus on the required quality. In addition to the Foundation’s Project Manager, independent Quantity Surveyor and Planning Supervisor services were procured.

The further appointment of Planning Consultant had been made at an earlier stage, in order to achieve as beneficial a Planning Consent (and Listed Building Consent) as possible. Separate ‘Change of Use’ (November 1997) and Full Planning Consents were obtained, the latter in July 1998, by which time the form of the project had been developed. Additional legal complexities had to be taken into account concerning the lease of the site, the treatment of the redundant Grade-1-listed church, construction in the graveyard, the archaeological implications, the views of English Heritage and the views of the City Council on matters such as tree preservation, conservation and the effect on the surrounding community. All these issues had to be resolved to the satisfaction of ACE as well as YEMF.

By Easter 1998, a full Professional Team was in place, together with funding, a Strategic Brief, a Condition Survey, a Tree Survey and an Outline Planning Consent. Design work could begin.

PROJECT STAGE. VALIDATION AND BRIEFING

The first act of the Project Manager (GTMS) was to assemble the available information for the Team, in the form of the ‘Client’s Outline Brief’ of 29 January 1998. This was a useful validation of the work done so far, and was the agreed basis of the subsequent briefing and discussion process. There followed the standard RIBA stages of work, firstly with a period of intense discussion with Delma Tomlin of the principles and objectives of the project.

In July 1997 the Church had been vacated by its former users, and the first notes were played to the Trustees by Anthony Rooley, the lutenist member of the Festival’s artistic advisory team. The immediate response of musicians, shared later in the autumn by the acousticians involved with the competing Professional Teams, confirmed that the acoustic of the standing building was so good that thoughts of internal partitioning should be abandoned in favour of an external extension, to house all the administrative and ‘greenroom’ functions that had been discussed during the architectural interviews. Discussions with the Planning Authority, English Heritage and the appointed archaeologists followed, and the principle of an annex to the church was accepted.

Stage C proposals

Because of the early difficulties over appointments, together with lease and planning negotiations, the programme for the work had slipped. It was reported to ACE in April 1998 that the Stage D report would be ready in July 1998 and that project completion was envisaged for November 1999. The first date was achieved, but delays in ACE approvals (and later in work on site) gave rise to a three-month slip in completion of the project, to February 2000.

A Stage C submission was not a condition of the Grant, but the Trustees felt that such an exercise would facilitate the all-important Stage D, as well as being a desirable step in itself. The Stage C submission resolved the space allocations for the various functions, and presented approaches to issues such as access for the disabled, landscape strategy, acoustic performance and treatment, the rebuilding of the roof of the church, the external materials for the annex, foundations in relation to trees, servicing principles, IT strategy and conservation philosophy. The context was provided by an initial cost report. All (or nearly all) of the questions raised in the Strategic Brief were addressed. Probably the only omission at this stage was the absence of a security strategy for the Centre.

Stage D submission and detailed design

The Stage C submission was approved by ACE in time for work on Stage D to begin to programme (May–July 1998). Again, the communication structure was centred on much informal discussion with Delma Tomlin, and formal Design Team and Client meetings, often focusing on specific issues or current aspects of the process. For example, in the course of Stage D much detailed acoustic provision was resolved (silent lighting and mechanical services, acoustic-quality doors), as was the structural engineering solution of the difficulties with the annex foundations (tree roots to be protected, in conflict with the need to minimise excavation in the graveyard).

The resulting report now added contributions reflecting the input of recording engineers, the Visual Artist, auditorium lighting specialists and the important report from the English Heritage architect. Variable auditorium layouts were also presented, and the whole scheme was subjected to audit by the Access Consultant. Almost (but not quite) too late, the Foundation’s Security Adviser’s report was received (8 May 1998), in time for inclusion as an appendix, covering aspects of personal security, risk assessment and management of security in relation to the Foundation’s business and activities.

The separate cost report at Stage D was an essential component of the package for ACE, whose condition had been that the quality and viability of the proposals must now be approved before permission could be given for further work. At the same time, an update of the Business Plan included in the Grant application was completed and the submission was the subject of a detailed presentation to the Trustees, who again commented at length on matters of detail, having enthusiastically endorsed the design solutions put forward and the overall quality of the proposals. The Trustees were also comfortable with the cost report, which reflected the increased cost of professional fees (as agreed at appointment) and the consequent adjustment of some heads of expenditure, notably the reduction to a minimum (by agreement with Customs and Excise) of the impact of VAT.

The Cost Report gave estimated building costs of £1,170,000, exclusive of all fees, furniture, equipment and VAT. Area costs were £1,081/m2 for the extension (335 m2), and £2135/ m2 for the existing church (282 m2). Included in the total were £100,000 for external works and £106,000 for contingencies.

The comprehensive Stage D report was submitted to ACE on 23 July 1998. There was then a delay of five weeks before the Arts Council was able to respond. Its response, on 28 August, was equivocal. On the one hand, the Trustees could proceed towards tender according to the proposals; on the other hand, various ‘issues’, vaguely defined, might prevent subsequent acceptance by ACE of any tender submitted.

ACE NEGOTIATIONS

Although there had been indirect expressions of concern over the long-term viability of the NCEM project as soon as it came under the purview of the project administration section of ACE (from as early as the autumn of 1997), no specific comment was made on this aspect until late August 1998, when Stage D and the Business Plan had been presented (and the associated resources spent).

It is worth reflecting that there was no reference to a requirement for a formal Business Plan in the Conditions of Grant; the only such reference was to ‘any further financial information that may be required’ and this was assumed to refer to formal accounts and standard reporting on project expenditures. Trustees had, however, established forward estimates of income and recurrent expenditure, and had developed their revenue-raising strategies for both grant aid and earned income from recording, conference hirings and the like. These requirements had been articulated in the Strategic Brief and properly provided for in the detailed plans.

In the response to the Stage D submission (28 August 1998), it was said on behalf of ACE that, whilst approval was given to go out to tender, there were a number of issues to be further addressed. If these issues were not satisfactorily addressed, then ‘the Arts Council will not be able to give final approval for you to issue a letter of intent, enter into any contracts or indeed continue to fund the scheme’. The issues were identified as long-term viability (principally focusing on maintaining the building and replacing equipment, coupled with a perceived risk of shortfall in projected income) and unspecified errors of omission or commission as regards the building project itself.

Faced with this situation, Trustees had a difficult decision to take. Should they proceed to tender stage, and spend a further £100,000 of partnership and ACE money in these uncertain circumstances? Or should they pause until the Business Plan issues had been further identified, and risk losing the project altogether? In the event they decided to press on.

Detailed design work was started in September 1998 and completed by December 1998, and the updated Business Plan was presented to ACE on 23 November, with a request for its early discussion. This request was not acknowledged. Tenders were due to be received in mid-February 1999, and there was a growing feeling of bad faith in requiring the team and tenderers to expend much effort on a project that remained uncertain even at this late stage.

In the response to the Stage D submission (28 August 1998), it was said on behalf of ACE that, whilst approval was given to go out to tender, there were a number of issues to be further addressed. If these issues were not satisfactorily addressed, then ‘the Arts Council will not be able to give final approval for you to issue a letter of intent, enter into any contracts or indeed continue to fund the scheme’. The issues were identified as long-term viability (principally focusing on maintaining the building and replacing equipment, coupled with a perceived risk of shortfall in projected income) and unspecified errors of omission or commission as regards the building project itself.

Faced with this situation, Trustees had a difficult decision to take. Should they proceed to tender stage, and spend a further £100,000 of partnership and ACE money in these uncertain circumstances? Or should they pause until the Business Plan issues had been further identified, and risk losing the project altogether? In the event they decided to press on.

Detailed design work was started in September 1998 and completed by December 1998, and the updated Business Plan was presented to ACE on 23 November, with a request for its early discussion. This request was not acknowledged. Tenders were due to be received in mid-February 1999, and there was a growing feeling of bad faith in requiring the team and tenderers to expend much effort on a project that remained uncertain even at this late stage.

CONSTRUCTION

After a very careful period of contractor selection, the patience and professionalism of the Team were rewarded by the receipt of excellent tenders. As noted in 2.3 above, the Stage D cost report anticipated tenders at the level of £1,170,000. The six tenders (from local and regional firms of repute and with conservation skills) ranged from £1,242,347 to £1,326,601, with four being bunched at the high end of the range and the lowest two within £1,500 of each other. After clarification, and the omission of certain provisional sums, the lowest tender could be recommended, from Simpson Construction of York, in the revised contract sum of £1,187,944.20, including contingencies of £103,450.

The contract was let in this sum and compensating savings for the slight excess over the target were made to other budget heads. The saving of some £55,000 between tender and contract sum was achieved principally by reducing the provisional sums for acoustic drapes throughout the project. These had been included as substantial allowances to achieve the acoustic brief, with special regard to speech; however, savings could be achieved because Simpson had its own joinery shop, and so could fabricate acoustic panels much more cheaply than the proprietary systems first anticipated. This exercise gave an early indication of the fruitful relationship that developed with Simpson as main contractor. Both their Construction Director (David Graves) and their Construction Manager (Andrew Gatenby) had conservation expertise, and the nominated Site Manager (Mark Cregan) had recently completed a project on the listed York Railway Station.

The Letter of Intent was placed with Simpson on 23 March 1999, envisaging a start on site on 6 April and a completion date 41 weeks later on 14 January 2000. This completion date was later than the November 1999 anticipated at Stage D, principally because of the delays experienced in negotiating with ACE. It was notable that the Professional Team maintained their programmed activities, despite the delays imposed by the funding body. At all events, the Foundation knew that its own essential timetable would be achieved if sufficient time could be given for an orderly occupation of the finished building from February 2000 onwards, in good time for the formal opening on 7 April 2000.

Tree roots had to be protected during the construction work

The high quality and developed state of the tender information led to a contract period with relatively few surprises or difficulties. The most substantial tasks were the repairs to the stonework, the rebuilding of the church roof structure to give the required sound insulation, and the provision of foundations for the new annex.

The first two of these were tackled at once, and rapid progress was made. Such problems as occurred in the contract were caused by the interaction between the preservation of tree roots, archaeological work in the burial yard, and the formation of strip foundations for the annex. These three factors combined to create challenging problems, especially because of the local authority’s insistence on extreme protective measures for the trees. However these problems were in due course overcome, through careful hand-digging and redesign of some foundations; but the cost was a programme slippage later quantified as a two week extension of the contract, and an increased foundation cost of some £20,000, met from contingencies. The foundations had been programmed by the contractor for completion on 26 August, but the last pour did not happen until 13 October, partly because a further week’s extension for wet weather had to be granted.

Once the foundations were complete, the pace of the work could increase dramatically, to the extent that the Site Manager, Mark Cregan, was controlling up to 60 operatives on the site in the later stages. Despite this, excellent standards were maintained, including for the electrical and mechanical services. A practical completion inspection on 18 February 2000 permitted occupation by the Foundation a few days later. The inspections led to the timely production of defects lists, and while these were long because of the rate of acceleration in the final weeks (some 100 architectural items, 90 services and 40 landscaping), they were in the main completed by the end of March.

Mark Cregan remained as a dedicated resource until the opening of the Centre, to the great benefit of the project. The quality of the manuals and equipment handbooks was also high, though three out of five volumes of information were not received until August. In addition, no great benefit was derived from an ‘induction day’ on 10 February into the use of the new equipment, because of poor professional organisation, and the situation was only saved by the continuing presence of Mark Cregan.

The finances of the contract were also closely controlled, with regular reports as to the projected final account figure being provided to Trustees. The July 1999 report (when little contingency expenditure had been incurred) anticipated an out-turn of £1,111,994, but this rose to £1,137,072 by November 1999, reflecting the extra expenditure on foundations (and on the acoustic insulation of the tower plant-room). But because of the control exercised, it was possible in November/December 1999 to instruct additional work items identified by the Foundation in the course of the contract period.

These items had to be authorised by the Monitor and ACE, but after further delays approval was given for expenditure to a total of £22,700 on a range of items, some of which were not a charge on the building contract, but had been identified in the course of business planning work. The additions included: churchyard gates, lighting and signs; refuse bins and telephones; extra fees relating to the tree work and additional items designed; exhibition equipment and a donors’ board; remote direction signage; and marketing material. Further items were deferred until the final account figure was established.

It was also anticipated at project completion that a further £22,700 would remain unallocated under the ‘residual contingency’ heading, held outside the building contract sum to meet unforeseen eventualities of whatever kind, given that the Foundation was not in a position to incur expenditure beyond the total project value (£2.025 million). In the event, ACE consent was eventually given to spend up to the project value, on items designed to ensure the viability of the Foundation over time. By the end of July 2000 a final account total of £1,195,000 was agreed between Simpson and the Quantity Surveyor, to include a number of items funded from budgets other than that for construction, once it became clear that there was no danger of the construction budget having been over-spent.

Despite the remaining concerns, the formal opening weekend of concerts and educational projects, starting on 7 April 2000, was a major success. The National Centre for Early Music was at once perceived as a major addition to the facilities for the study and performance of early music, which lay at the heart of the venture started six years earlier.

POST-PROJECT STAGE

RE-STATEMENT OF NEED

The revisiting of the Business Plan in the course of the construction contract did not in the event result in any change in requirements. The principal planned activities remained unchanged from the Strategic Brief, even if their mix might change in reality. The variety of musical uses (from large performances and musical drama to smaller recitals and classes) will be supplemented by revenue-earning conference bookings and recording sessions, for all of which the demand was quickly demonstrated. Education work has already resulted in community activity and a programme of special-education projects in conjunction with the City of York Council. Much initial effort went into the hiring of the Centre to the organisers of the York Millennium Mystery Plays for rehearsal use, with great success; at the same time preparations for the July 2000 Early Music Festival, the first in its new home, moved forward quickly.

A small embarrassment was the speed with which the ‘ration’ of up to 12 public musical performances per year was used up. This restriction was imposed as part of the planning process and it was necessary to submit a further application in order that it be lifted. In the event, the extent of community involvement in and use of the Centre, together with the neighbours’ experience of its use in practice, overcame the concerns that had led to this constraint – the local ‘Neighbourhood Forum’ voted unanimously that all restriction be lifted. A full Licence for Public Entertainment was granted (the requirements having been incorporated in the Brief) and an initial omission was corrected in that a restricted Justices’ Licence was granted, without any structural or physical implications. A further rectified omission was the granting of a Theatre Licence, again without physical implication.

There is mounting evidence for the belief that, as anticipated, the Centre will provide an invaluable national and international resource for early music education, research and performance, supplemented by appropriate revenue-raising uses. The Lottery Grant has enabled a properly resourced capital project, relieving the Foundation of the burdens of financing the conversion and extension work, which it alone could not have borne, had it been necessary to borrow the capital. This must be the central message for arts Lottery projects.

The completed Centre has won widespread admiration. For example:

‘A wonderfully welcoming building’

Glyn Russ, Administrator, Early Music Network

‘It almost seemed as if [St Margaret’s] had never been out of use at all’

The Archbishop of York

‘The building is wonderful. It’s a very fine medieval church with a sympathetic extension. The real joy is what goes on inside ... To have a place of this quality in York is obviously something of real importance to music-making in the city and surrounding area’

Chris Smith MP, Secretary of State for Culture, Media and Sport

‘The new works undoubtedly herald musical riches aplenty in this wonderful building’

Yorkshire Evening Press

‘The planners were at first cautious about the idea of new build, but were eventually persuaded, because of the unobtrusive nature of the [annex] structure which is set snugly within the churchyard walls’

Building Design

‘With such a high roof, it is surprising that the sound is so tight and well-focused, and quite different to the reverberation-laden ambiance enjoyed by many early music groups’

Yorkshire Post

‘It’s a Grade-1 listed church which is going to become a centre for early music of international standing and importance. I think that is very exciting’

Alan Howarth MP, Minister for the Arts

EVALUATION OF PROCESS

The Foundation believes it has successfully completed the process of generating and managing a substantial capital project on budget and to an outstanding quality (see 3.3 below). The process has taken longer than envisaged both at inception and at Stage D; in the former case a necessary change in the Professional Team and the general complexity of the project led to a four-month delay; after the Stage D submission, two further months were lost in ACE negotiations, and a further month through contract extensions. Nonetheless it is the Foundation’s belief that for this project, cost and quality were paramount, while time was not of the essence.

The process was greatly assisted by the appointment of an outstanding Project Manager – Jim Boothroyd of GTMS. That competitive appointment (the requirement for which was, in the event, the principal contribution of Bovis as Build Monitor) assisted the Foundation immeasurably, since it was otherwise lacking in hands-on experience of managing the multitude of organisational and technical complexities that have been reflected in this evaluation. The attainment of the major goals would not have been possible without the professionalism and commitment of Jim Boothroyd.

The favourable financial out-turn is a reflection of the management skills of the Project Manager, the Quantity Surveyor and the Professional Team as a whole, in designing to a fixed budget. A small under-spending could be reallocated to other long-term aspects of the project. The overall outcome compared to the budgets at Grant Award and at Stage D was:

Capital budget |

Grant estimate

|

Stage D estimate

|

Project out-turn

|

|

Building work and fees (including inflation and contingency) |

1,581,000 |

1,616,000 |

1,624,000 |

|

Furniture, equipment |

144,000 |

93,300 |

97,731 |

|

Visual arts |

35,000 |

35,000 |

|

|

Music commissions |

60,000 |

60,000 |

50,000 |

|

Instruments |

120,000 |

124,011 |

120,000 |

|

Management |

120,000 |

96,689 |

98,269 |

|

Sub-total |

300,000 |

315,700 |

303,269 |

|

Total project cost |

2,025,000 |

2,025,000 |

2,025,000 |

The process was greatly assisted by the preparation of an agreed Strategic Brief and its subsequent conversion by the Professional Team into a validated Project Brief. This activity gave a shape and a sense of shared ownership, which characterised the entire project. Sub-briefs were provided for such areas as acoustics, security, visual art, and access, to the benefit of the scheme, although the security brief could (as noted in 2.3 above) have benefited from earlier preparation.

The process of appointing the Professional Team worked extremely well, after the early difficulties described in section 1.3 had been overcome. Once the team was established (February 1998), its composition did not change, and the leadership provided by van Heyningen and Haward was exemplary. The expertise in the role of Lead Designerprovided by that practice was an inspiration to the entire team, but it was also beneficial for the single point of responsibility, from the Trustees’ point of view, to be vested in the Project Manager, with the broad oversight of the project as a whole. The briefing and detailed implementation roles undertaken by Delma Tomlin, as Administrative Director and voice of the Foundation, ensured that sight of the project objectives was never lost.

The reception area, National Centre for Early Music, August 2000

It has to be said that ACE administrative processes did not contribute positively to the project after the initial assessment stage. More realistic caseloads for individual officers, together with the contribution by them of active help and advice, would be more productive than the uncertainty and delay that the Foundation experienced, for reasons that remained undefined. The absolute need for accountability in the use of public funds is accepted and endorsed, but the Foundation feels that project regulation could be achieved with added value, through dialogue and the transparent adoption of unambiguous procedures.

EVALUATION OF THE PRODUCT

POST-CONSTRUCTION EVALUATION

The self-evident outcome of the project is an overriding sense of design quality and of a unity and integration of purpose, appropriate to a ‘national centre of international quality’, as envisaged at the outset by the ACE Assessor and by the Foundation. The essential acoustic qualities have been achieved, as indicated in the valuable guidance notes provided by Arup Acoustics:

Activity |

Acoustic boxes: absorption exposure |

Drapes: absorption exposure |

Acoustic qualities of space |

Time range (seconds) |

|

Large choral |

All boxes closed |

All drawn back |

Highest reverberation, warmth, spaciousness |

2–2.6 |

|

Music recitals |

All boxes closed |

All drawn out |

Even balance between clarity and reverberation; discrete sounds stand apart clearly, but ample reverberation |

1.5–1.8 |

|

Small ensembles |

25% of boxes open |

All drawn out |

Balance towards clarity (assume 110+ padded seats) |

1.4 |

|

Opera/musicals |

75% of boxes open |

All drawn out |

High degree of clarity, modest reverberation |

1.2 |

|

Lectures/speech |

All fully open |

All drawn out |

Sound absorbent space, giving maximum clarity for speech |

1.0 |

The early responses of performers and audiences have been entirely favourable, and further evidence will emerge in the course of use in all the various configurations. Other important early assessments include financial confidence, a sense of personal and physical security, a warm and welcoming environment, and an excellent response from users with disabilities.

On the other hand, minor criticisms can be made of matters such as the security system omissions that had to be remedied (arising from the unavailability of the Foundation’s security consultant at the return of tender stage) and minor failings in the disabled provisions. This latter was due to the consultant not having been invited to vet working drawings; the extent to which provision for the disabled was a central concern for YEMF may not have been adequately communicated. However, no long-term issues arose that are not capable of resolution. A general point does remain in that, while the ‘core’ Professional Team members were unusually well integrated, there were ‘supporting’ roles that appeared more detached, such as the Disability Adviser and the Visual Artist. The Security Adviser and the Lighting Consultant also provided advice at appropriate stages.

In some respects an evaluation is premature, in that not all systems have yet been fully used and it is too early to be certain of matters such as the stability of environmental conditions for all instruments. The ndications are that the grass roof of the annex and the underfloor heating in the Church will be fully effective; however the Church is subject to a period of drying out of the saturated stonework after decades of rain entry and it has been necessary to make financial provision for a further coat of lime-wash, at the end of the defects liability period.

POST-OCCUPANCY EVALUATION

Eighteen months after its formal opening the Centre has passed almost every test with flying colours. Its acoustic qualities include the flexibility described in 3.3.1 above, the nearly total exclusion of external noise, and the containment within the building (to the relief of neighbours) of even the loudest music-making, including pop-music rehearsals. The architectural design and layout have met the needs of a wide range of artists and audiences, with performers ranging from the summer and Christmas festivals, to youth theatre, Japanese traditional music, the Digital Arts Festival and the contemporary York Late Music Festival. Enthusiastic responses have come from all participants.

The supporting commercial activities are for the most part developing as planned, with substantial use as a recording studio (income target £8,000 p.a.) by hirers such as the BBC World Service, BBC Music Live, and individual artists and composers. The conference and meeting business (income target £5,000 p.a.) is developing well, with repeat bookings from York Civic Trust, the Royal Society of Arts and the North East Early Music Forum. Substantial marketing work is being undertaken, given the long lead-times of most conference organisers. The Foundation’s core education programme is also making full use of the facilities for workshops that have involved music, dance, flag and mask-making and a recreation of the Commedia dell’Arte.

Any project evaluation must inevitably record a few failings, as well as the man successes. For example, the grass roof to the annex does not give rise to structural problems, but the vegetation has been very unsatisfactory (long and weedy) and total replacement may be needed. Furthermore, the beautifully conserved South doorway has suffered surface scaling, and powdering is evident across the capitals, columns and inner roof. This is due to salt movement within the stone and it seems that little effective action is possible. There were also an inevitable number of minor faults picked up at the end of the defects liability period, but these have for the most part been quickly remedied.

It can generally be said that the detail of the briefing and planning processes used from the inception of the project allowed thought, discussion and care to be given to all the specifications, so that very few surprises or disappointments were encountered at occupation, and cost and time overruns were avoided. These are, however, early impressions and it would be valuable to carry out a full post-occupancy evaluation, say two years after the completion of the project.

EVALUATION OF THE PRODUCT

The Strategic Brief called for a welcoming building, worthy of its setting in the City of York, if it was to fulfil its artistic and cultural objectives. The appearance of the completed building meets this brief, even if there are features of the physical approaches that are outside the Foundation’s control. More thought is needed, in conjunction with the Council, as to how further regeneration work can be associated with the Centre’s role. The achievement of the required ‘memorable quality’ will be an essential pre-requisite for longterm success and viability, if repeat performers and customers are to be attracted to Foundation activities.

All the initial evidence is that the necessary quality has been provided, but active management will be required to capitalise on that good start. The establishment of the partnerships with the University, the Minster and the York community, spoken of in the Foundation’s plans, will be further necessary components in setting the Foundation’s longterm direction, building on the success of the Festival and the goodwill and support of the community and the Local Authority. For immediate purposes however, it is believed that the performance of the Professional Team, client and contractor have contributed to a highly successful capital project, from which all the participants have learned, and which has commanded their enthusiasm, commitment and affection. The whole team was rewarded by the announcement of a national RIBA award in July 2001 and by the inclusion of the project in the shortlist of the Crown Estates Conservation Award.

CONCLUSIONS AND LESSONS FOR THE FUTURE

A number of factors contributed to the project’s success (despite the uncertainty and delay created by the processes of the funding body):

The Foundation appointed a small group of Trustees to oversee the project, with appropriate legal, financial and project administration skills.

A clear Strategic Brief was established at the outset, and adhered to.

A team was selected that was notable both for its design skill and for its ability to provide integrated solutions after careful client discussion.

An experienced Project Manager and the Director of the Foundation were granted full authority to act on behalf of the team and the client respectively.

Cost and progress reporting were timely and to an appropriate level of detail at each stage, giving excellent financial control to all participants.

Communication with and between the Professional Team, and with the Contractor, was of a high quality.

Contractor and Sub-Contractor selection processes were detailed, and based on individual references, rather than interviews alone.

Programmes were realistic and a correct balance was struck between the three variables of time, cost and quality.

The difficulties encountered in the preparatory and contract stages were addressed by the client and the Professional and Contract Teams, acting together, with each fulfilling an appropriate role to the benefit of the project.

APPENDIX

Participants, Professional Team and Advisers

van Heyningen & Haward Architects

Birkin Haward Partner in Charge

Candy Fraser Project Architect

Lorna Davies Project Architect

Gardiner & Theobald Project Services

Jim Boothroyd Project Manager

Martin Stancliffe Architects Consultant Architect

Martin Stancliffe Partner

Linda Lockett Project Architect

Rex Procter and Partners Quantity Surveyors

Ian Armitage Partner

David Ribbons Project Surveyor

Price & Myers Structural Engineers

Sam Price Partner in Charge

Fiona Cobb Project Engineer

Max Fordham & Partners Mechanical & Electrical Engineers

David Littler Project Engineer

Angus Melville Project Engineer

Arup Acoustics Acoustic Consultants

Dr Raf Orlowski Acoustic Consultant

Juliette Milner Acoustic Consultant

Livingston Eyre Associates Landscape Architects

Katie Melville Project Landscape Architect

Laura Stone Project Landscape Architect

Simpson (York) Ltd Main Contractor

Ron Gatenby Managing Director

David Graves Construction Director

Rod Wileman Quantity Surveyor

Mark Cregan Site Manager

Bovis Program Management ACE Build Monitor

Paul Kelly Project Manager

York Archaeological Trust Archaeological Consultant

Peter Addyman Director

GTPS Planning Supervisor

Iain Miller

Centre for Accessible Environments Access Consultants

Brian Towers Project Consultant

Hanna Conservation Sculpture/Conservation

Seamus Hanna Conservator

Portland Planning Consultants Ltd Planning Consultants

Janet O’Neill Project Consultant

Burrows Davies Stone Sub-Contractor

Barley Studios Church Glazing

Keith Barley Glazier

Stuart Sutcliffe RIBA Architectural Adviser to the Trustees